A Deep Dive into Modern New Zealand Extinctions Part 1

New Zealand's Historical View on Extinction

Extinction isn't something we talk about much as New Zealanders. When we do, it's usually in the past tense. After all, isn't extinction a thing of the past? An unfortunate tragedy that long ago happened to the Moa, Haast Eagle and Huia? We tend to view modern conservation efforts with a sense of real pride.

We're a nation of outdoorsmen, and locally driven conservation projects are a major part of our cultural identity. Our pest control efforts are world leading; moreover, we pulled both the Kākāpō and Takahē back from the brink of extinction. Which is precisely why the actual state of our flora and fauna would shock many of us.

What we often fail to consider is the scale of our nation's biodiversity. New Zealand has been ecologically isolated from the rest of the world for eighty million years. Of all the places on earth, only Madagascar has been isolated for longer. The majority of our native species are unique to our nation, and eighty percent of them are at risk of extinction. That's not just a risk in the future, but a real risk right now.

It might shock the average Kiwi to learn that we're seeing species going extinct right now. Not just a few either. We are losing species year on year, and it's projected that things will only continue to get worse. They say that to change the future, we must learn from the past. Therefore it seems important to take a deep dive into modern extinctions and what causes them.

Extinction in NZ is a difficult topic

The Tragic Tale of the New Zealand Grayling

It might seem odd that we are beginning with the extinction of fish species. They're hardly a poster child for conservation. Aside from Trout or Salmon, the average New Zealander would probably struggle to name a single freshwater fish. So when we approach the New Zealand Grayling, it's important we start from the beginning.

Grayling are a species of fish found predominantly in European rivers. Māori called it the Upokororo and considered it an important food source. When Europeans colonised Aotearoa, they were both widespread and abundant. It was a smaller silver fish, whose habitat was predominantly clean, cold, freshwater streams, particularly in forested areas, both across the North and South Islands.

The New Zealand Grayling is not a true Grayling. Biologically, it's an entirely different species. However to European settlers, its physical characteristics were so similar that the name stuck. The key difference appears to have been that it lacked a dorsal fin that European Grayling had. Populations seemed stable until around 1870, when a sudden crash was recorded. For unknown reasons, over the space of three or four years they suddenly became rare.

The range of the Grayling contracted quickly. Within a few years, they could only be located in the most remote regions of New Zealand. North Island strongholds seemed to be located around both the Wairarapa and East Cape. While down South they hung on in the West Coast.

It's hard to pinpoint an exact date of extinction. In part due to how poorly studied Grayling were, but also due to the remoteness of the regions which they last inhabited. Their disappearance was not immediately recognised by either the government or the public; nor would it be for decades to come. Reports indicate a presence on both islands until at least the early 1920s, though the final sighting would be in just 1924.

No colourised photographs of the NZ Grayling exist. Instead pictured is a European Grayling

The New Zealand Grayling's Disappearance

Modern research indicates they hung on for much longer, though. Government archives list possible captures in the 1930s. Farmers on the West Coast reported seeing a grayling in 1939. Further south, in the remote rivers inland from Bruce Bay, sightings would persist right through to the 1950s. Recent modelling suggests a probable extinction date around 1972.

It's not completely clear what caused the grayling to rapidly decline. They were poorly studied, and modern researchers therefore have to speculate to some degree as to what happened. Several possibilities do seem likely, key among them being the introduction of trout into waterways in 1867. Grayling may have struggled to adapt to the increased competition for resources.

There's also some evidence to suggest that trout may have carried pathogens that caused mass die-offs of grayling populations. Similar die-offs were observed in Australian grayling populations when they encountered trout for the first time.

Another factor may have been the way grayling bred. Spawning probably only occurred under a very specific set of conditions and may have been limited to a select few locations around the country. Freshly hatched grayling would then populate other streams and rivers from these locations. The collapse of even a limited number of these breeding sites would have contributed to a nationwide collapse of upokororo.

Though the full causes of extinction may never be understood, it does seem likely that trout were the major contributing factor. Official protection for grayling was not introduced until 1951—thirty years after the last official sighting. While they probably still existed, the causes of their decline were not understood until recently. Even if they had been rediscovered in the following years, it seems unlikely they could have been saved.

It seems unlikely the NZ Grayling could have been saved.

The Legacy of the Laughing Owl

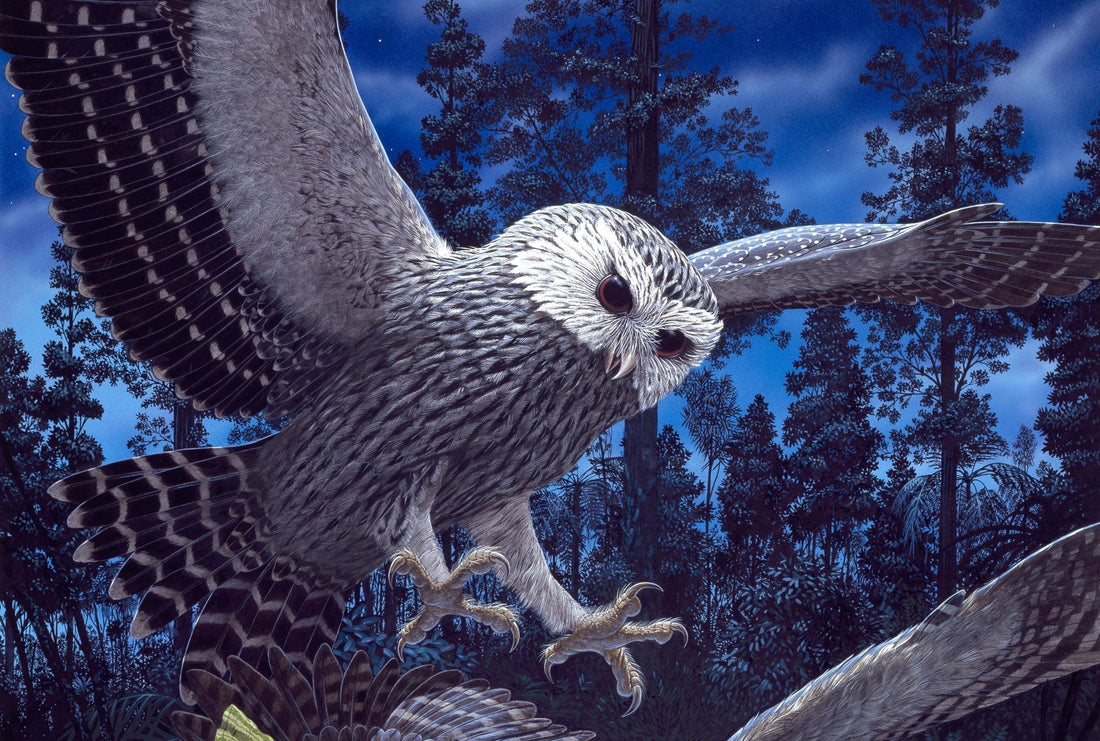

The laughing owl was well known for its haunting nighttime scream. To be the last person alive to witness a species must be a terrible thing. I wonder if the man who found the last laughing owl felt that way. Its corpse was discovered on the side of a road by a South Canterbury farmer in 1914, hit by a vehicle that hadn’t even bothered to stop. An unglamorous end for a unique species.

The laughing owl terrified early explorers at night. Their maniacal, haunting screams and calls were compared to the sound of children screaming. While widely dispersed over both the North and South Islands, it seems to have been the dry Canterbury backcountry that served as a stronghold for the species. Nesting in limestone caves, they fed predominantly on native birds, though part of their diet also consisted of rats and mice.

Unsurprisingly, Europeans were fascinated by them. In the late 19th century, zoos and private collections in Europe received dozens of live specimens. Tragically, despite both adapting well to captivity and, on occasion, producing eggs, no proper breeding programme was ever set up. By the 1890s, they were becoming rare.

It seems likely that introduced predators such as stoats and ferrets took their toll on the laughing owl population. Their disappearance from regions near human settlement meant that most Europeans believed they were doomed to extinction.

Sadly, this belief did not translate into action, and the laughing owl was last 'officially' sighted in 1914, when the dead specimen in Canterbury was discovered.

The Laughing Owl officially became extinct in 1914

The final Chapter of the Laughing Owl.

It seems likely that the laughing owl was not truly gone. In fact, it was probably widespread across most regions of the South Island for another two decades. Ornithologists have gathered more than a dozen sightings believed to be genuine from this period. Even after the 1930s, reports were still common.

In 1939, laughing owls were reported by farmers in the Aniseed Valley near Nelson. The famous scientist Dr Orbell wrote in 1951 that he knew of the nesting site of a pair in Fiordland. This is particularly remarkable, given that he had only just rediscovered the takahē, which had also been considered extinct. Though it may have been his experiences with the takahē that caused him to choose a different path for the laughing owl.

He seemed to have become jaded by the response he received from the public and believed they were best left alone. The following year, another Fiordland sighting would come to light, and in 1956, Hall-Jones, a reputable author well known for pioneering kākāpō research, would come forward with an additional Fiordland sighting. Abandoned nests and egg fragments would continue to be reported in Canterbury until the end of the 1960s.

Backcountry stations from the region would report maniacal screams at night several times in the following decades. In the 1980s, two separate reports would come in from near Arthur’s Pass—tantalisingly, they were just ten kilometres apart. Another would come from Stewart Island, where a now-lost photograph of a laughing owl was taken and confirmed to be authentic by experts.

However, since then, there has been nothing, and it seems likely that in the last forty years, the laughing owl has finally been lost forever.

The laughing Owl probably slipped into extinction in the last forty years

Lost in Isolation The South Island Brown Teal

The South Island brown teal was so rare that I can’t even find any photos of it. It doesn’t have a Wikipedia page—and may never have been formally described. It is one of two native birds currently listed by the Department of Conservation as ‘Data Deficient, possibly extinct.’

We know that 200 years ago, the brown teal was probably our most widespread water bird. However, introduced predators soon put an end to that. Populations plummeted, and they tend to thrive only in areas with extensive predator control.

Milford Sound is essentially a wildlife haven, surrounded on all sides by tall mountains. Birdlife in the region would have had limited genetic flow outside the catchment. Each valley is so isolated that it’s believed they all evolved unique species of skink. This is fascinating when you realise each population was only a few kilometres apart and yet isolated for thousands of years.

The birdlife of the region is equally unique. It’s believed that takahē lasted longer here than anywhere else in New Zealand. Kākāpō in Sinbad Gully 'boomed' with a different 'dialect' than other parrots and were known to carry a rare yellow genetic allele too.

The Arthur River feeds into Milford Sound from the south. Over the years, many had observed that ducks residing in the river had a range of characteristics not found in other teal. Given the remote location of the teal and the focus on other conservation projects, this was never followed up until the late ’80s and early ’90s.

Genetic testing would reveal what had long been suspected—that teal on the Arthur River were a separate species. However, this would not be enough to save them. At the time, the newly created Department of Conservation was stretched thin. Funding barely existed, even for flagship species such as the kākāpō and takahē.

Similar to the other animals in here, no known photos exist of the South Island Brown Teal. We used photos of Teal instead.

The Last Days of the South Island Brown Teal

The plight of a new species of duck wasn’t enough to capture the imagination of scientists or the public. No identifiable immediate threats were observed, and for the most part, the newly discovered South Island brown teal was forgotten. Local rangers would occasionally observe them, but no other action was taken.

No information exists as to an exact extinction date. Instead, there was a gradual realisation that teal hadn’t been seen for a long time. Data was only collated in 2017, and we lack almost thirty years of information. The last confirmed sighting was in the 1990s, and recent searches have uncovered no trace of the birds.

The similarity of the South Island brown teal to other ducks may have played a part in its downfall. A lack of funding and interest from either the public or scientific sectors in the emergence of a new species of bird was also a major contributing factor.

Given the attention other new species have received in recent years, it’s truly remarkable how little attention the teal received. No funding was set aside to study them, no newspapers ever wrote about their discovery, and no government department or scientific authority saw it as their responsibility to rescue them.

The Milford Track has thousands of people walking it yearly, yet despite this, probably fewer than a hundred New Zealanders were ever aware of the existence of the South Island brown teal. Unless new evidence comes to light, it seems we’ve lost this unique species forever.

We lost the South Island Brown Teal in the last thirty years

The Urgency of Conservation for New Zealand's Wildlife

None of these animals are recoverable, but we can take note of what contributed to their loss. Competition with introduced species, parasites, and sensitivity to changes in breeding habitat probably killed off the NZ grayling. Introduced predators and an unwillingness to follow up on reports probably doomed the laughing owl.

Meanwhile, a lack of funding killed off the South Island brown teal. It’s heartbreaking that none of these species died in the distant past. Instead, their extinctions happened right before us, and we did nothing. There are living people who have seen all of these animals.

Maybe the lesson we need to learn is that if we don’t act with urgency for the wildlife we’re losing today, no one else will.

Learn more about an additional three modern extinctions here.

If you won't act. Who will?

Enjoy this style of investigative journalism? Take a moment to learn about how political infighting nearly lost us the iconic Kakapo.

Support us by purchasing from our online store which allows us to devote more time to stories like this.